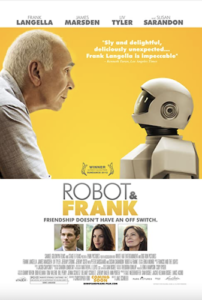

Today, I want to talk about Robot and Frank, one of the most realistic movies about AI and robots you’ve never heard of. In this underrated gem, an aging burglar receives a robot butler. What can possibly go wrong ?

But first some context: most AI research today focuses on improving the performance of AI systems. That means making the system better at what it is designed to do. For example, we seek to improve self-driving cars so that they can handle a broader set of road, weather, and traffic conditions; improve digital assistants so that they better understand our spoken requests and handle our transactions; or improve in-home assistive systems so that they better anticipate, help, organize, and manage an aging adults’ needs.

All such systems still face technical hurdles (how to recognize a never before seen obstacle on the road, how to determine whether an open door is a health risk), but they also face unique sets of ethical, legal, and policy challenges. As they become more and more competent, we need to shift from “can it do this?” to “should it do this?”

That is the question Robot and Frank addresses head on.

In a world where AI systems and robots take the role of butler, companion, helper, and in-home-care nurse for aging adults, what is the role of family members? The community? The medical professionals?

Robot and Frank does not provide pat answers. Instead, it introduces a robot with believable physical capabilities—and an AI system more competent that today’s tech but not jarringly so—and drops it in the middle of a somewhat dysfunctional family. After some initial resistance, Frank accepts the robot butler his son gives him, only to realize the opportunities it provides may extend beyond helping with house chores.

From that simple premise, Robot and Frank explores key ethical dilemmas in current AI research:

- Is it acceptable to offload personal interactions to a robot, and if so under what conditions?

- Is it acceptable for a robot to nudge a human’s decisions (modify the person’s decisions with incentives)?

- Is it acceptable for a robot to use deception (nudges that may be based on falsehoods)?

- Is it acceptable for a robot to break the law if the harm can be mitigated and if doing so helps the person for whose well-being it is responsible?

No matter how you may have answered these questions, we can agree that in many cases, the answer is closer to “it depends.” The key success of Robot and Frank is in how it makes it absolutely clear these questions cannot be answered without contextual grounding.

There is no blanket answer for what an AI should or should not do because there is no such thing as “an AI.” If you were to ask me whether it is ethical for a chess-playing AI to intentionally lose to a child on occasion to keep them interested in chess, I’d say yes. That’s both a nudge and a deception, but by understanding the context, we may accept it as benign.

But modifying that question ever so slightly takes us to situations where we’re uncomfortable with the nudge or deception. For example, replace “child” with “aging adult” an it’s already more troublesome; then replace “chess” with “memory games” and you’re in the middle of the ethical dilemma about whether to disclose the rate of their cognitive decline to an aging adult.

While grappling with these issues, Robot and Frank is more buddy movie than sci-fi thriller. It works because it makes you question what a robot’s role ought to be in a society where more and more aging adults feel isolated, and how much our familiarity with a robot may change our interpretation of its actions or intentions.

In the end, Robot and Frank is more about us than robots, but provides a nice reminder that a robot need not time travel in an attempt to wipe out humanity to make us face difficult questions.